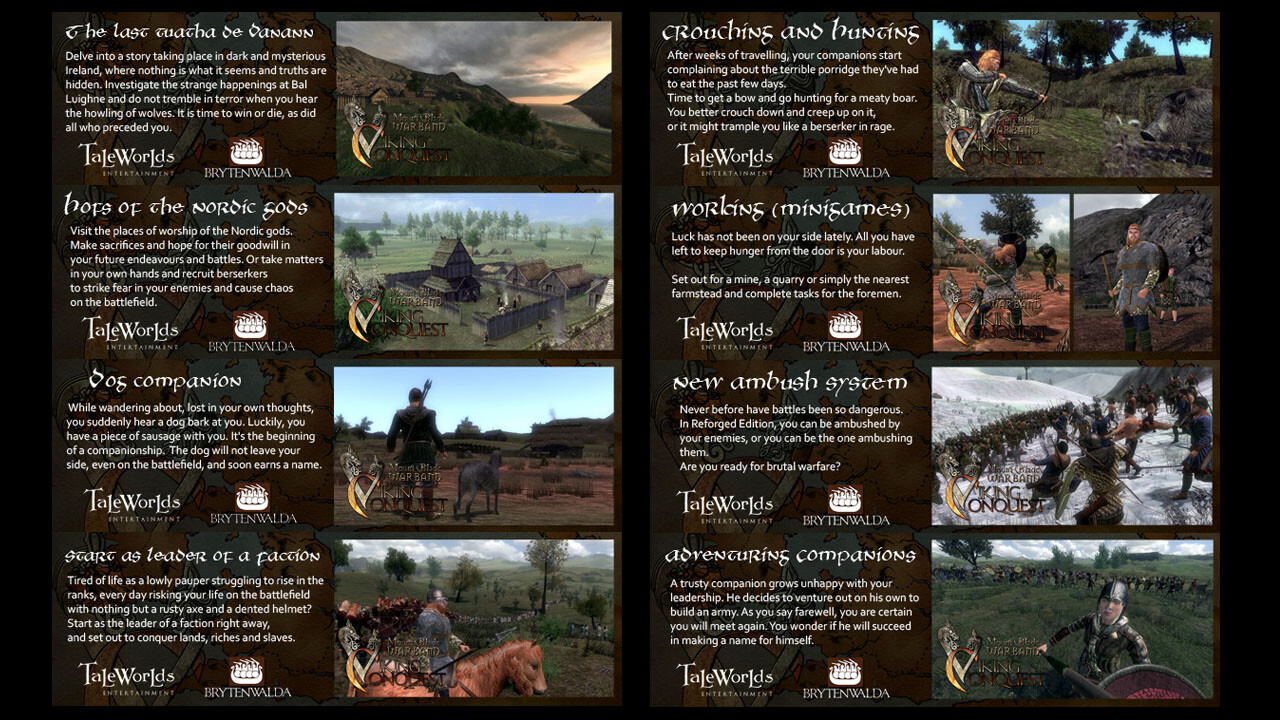

M&b Warband Serial Key 1.173

Notice: California WIC is open during the federal shutdown and stores will continue to accept WIC checks. Local WIC office hours of operation vary during holidays. Create an account or log into Facebook. Connect with friends, family and other people you know. Share photos and videos, send messages and get updates.

noun,pluralM's or Ms,m's or ms.

RELATED CONTENT

Definition form (2 of 17)

Definition form (3 of 17)

Definition form (4 of 17)

Definition form (5 of 17)

Symbol.

Definition form (6 of 17)

Origin of Mac-

Definition form (7 of 17)

Definition form (8 of 17)

Definition form (9 of 17)

Definition form (10 of 17)

Definition form (11 of 17)

Origin of m.

1Definition form (12 of 17)

Origin of m.

2Definition form (13 of 17)

Definition form (14 of 17)

Origin of M.

1Definition form (15 of 17)

Definition form (16 of 17)

Definition form (17 of 17)

noun

Origin of mu

Examples from the Web for m

“I´m now writing to you from goat heaven,” he lamented on the blog he maintains.

Sweden’s Burning Christmas Goat|Nina Strochlic|December 25, 2014|DAILY BEASTA third cabinet member used public funds to pay in an S & M bar.

Japan’s Nasty Nazi-ish Elections|Jake Adelstein|December 12, 2014|DAILY BEAST“[M]any a headband was soon stained red,” noted a TIME cover story from 1964.

‘Argo’ in the Congo: The Ghosts of the Stanleyville Hostage Crisis|Nina Strochlic|November 23, 2014|DAILY BEASTHe tells us that “[m]id-December in New York City is magical.”

Andrew Cuomo Ignores Rural New York|David Fontana|November 8, 2014|DAILY BEAST

Perhaps that S M bar trip was actually a useful political lesson after all.

‘Whip it!’ Japanese Prime Minister Abe’s Cabinet Of Horrors|Jake Adelstein|October 24, 2014|DAILY BEASTQuerido Compadre,—Mucho m'ha alegrado el buen termino de sus trabajos literarios que V.M. me participó.

Exercises containing the letters 'M' and 'N' will give this effect.

Military Instructors Manual|James P. Cole and Oliver SchoonmakerNo, m'm, you must talk through the bars, but I won't disturb you.

The Third Degree|Charles Klein and Arthur Hornblow'M's'u' has been very sick,' she imparted, speaking slowly, as though selecting her words.

As you have no butler, M'm, I presume you will wish me to act as sich.

A Little Dinner at Timmins's|William Makepeace Thackeray

British Dictionary definitions form (1 of 14)

nounpluralm's, M'sorMs

British Dictionary definitions form (2 of 14)

British Dictionary definitions form (3 of 14)

symbol for

- mature audience (used to describe a category of film certified as suitable for viewing by anyone over the age of 15)

- (as modifier)an M film

Mount And Blade Warband Serial Key 2018

abbreviation for

British Dictionary definitions form (4 of 14)

prefix

British Dictionary definitions form (5 of 14)

prefix

British Dictionary definitions form (6 of 14)

abbreviation for

British Dictionary definitions form (7 of 14)

abbreviation for

Word Origin for M.

British Dictionary definitions form (8 of 14)

prefix

Mount And Warband Serial Key

British Dictionary definitions form (9 of 14)

contraction of

British Dictionary definitions form (10 of 14)

usage

British Dictionary definitions form (11 of 14)

noun

British Dictionary definitions form (12 of 14)

British Dictionary definitions form (13 of 14)

abbreviation for

British Dictionary definitions form (14 of 14)

prefix

Word Origin for Mac-

Medicine definitions form (1 of 5)

Medicine definitions form (2 of 5)

abbr.

Medicine definitions form (3 of 5)

Medicine definitions form (4 of 5)

n.

adj.

Medicine definitions form (5 of 5)

Science definitions form

| M | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Fritz Lang |

| Produced by | Seymour Nebenzal |

| Written by | Fritz Lang Thea von Harbou |

| Based on | A newspaper article about serial killer Peter Kuerten by Egon Jacobson |

| Starring | Peter Lorre Otto Wernicke Gustaf Gründgens |

| Music by | Edvard Grieg |

| Cinematography | Fritz Arno Wagner |

| Edited by | Paul Falkenberg |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Vereinigte Star-Film GmbH |

Release date | |

Running time | 111 minutes[1] |

| Country | Weimar Republic of Germany |

| Language | German |

M (German: M – Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder— M – A City Searches for a Murderer) is a 1931 German drama-thriller film directed by Fritz Lang and starring Peter Lorre. The film was written by Lang and his wife Thea von Harbou and was the director's first sound film.[2]

The film revolves around the actions of a serial killer[3] of children and the manhunt for him, conducted by both the police and the criminal underworld.[4] Now considered a timeless classic, the film was deemed by Lang to be his magnum opus.[5][6]

- 3Production

Plot[edit]

A group of children are playing an elimination game in the courtyard of an apartment building in Berlin[7] using a chant about a murderer of children. A woman sets the table for lunch, waiting for her daughter to come home from school. A wanted poster warns of a serial killer preying on children, as anxious parents wait outside a school.

Little Elsie Beckmann leaves school, bouncing a ball on her way home. She is approached by Hans Beckert,[8] who is whistling 'In the Hall of the Mountain King' by Edvard Grieg. He offers to buy her a balloon from a blind street-vendor and walks and talks with her. Elsie's place at the dinner table remains empty, her ball is shown rolling away across a patch of grass and her balloon is lost in the telephone lines overhead.[9]

In the wake of Elsie's disappearance, anxiety runs high among the public. Beckert sends an anonymous letter to the newspapers, taking credit for the murders and promising that he will commit others; the police extract clues from the letter, using the new techniques of fingerprinting and handwriting analysis. Under mounting pressure from city leaders, the police work around the clock. Inspector Karl Lohmann instructs his men to intensify their search and to check the records of recently released psychiatric patients, focusing on any with a history of violence against children. They stage frequent raids to question known criminals, disrupting underworld business so badly that Der Schränker (The Safecracker) calls a meeting of the city's crime lords. They decide to organize their own manhunt, using beggars to watch the children.[10] Meanwhile, the police search Beckert's rented rooms, find evidence that he wrote the letter there, and lie in wait to arrest him.[11]

Beckert sees a young girl in the reflection of a shop window and begins to follow her, but stops when the girl meets her mother. He encounters another girl and befriends her, but the blind vendor recognizes his whistling. The blind man tells one of his friends, who tails the killer with assistance from other beggars he alerts along the way. Afraid that Beckert will get away, one man chalks a large 'M' (for Mörder, 'murderer' in German) on his palm, pretends to trip, and bumps into Beckert, marking the back of his overcoat.[11]

Once Beckert realizes that the beggars are following him, he hides inside a large office building just before the workers leave for the evening. The beggars call Der Schränker, who arrives at the building with a team of other criminals. They capture and torture one of the watchmen for information and, after capturing the other two, search the building and catch Beckert in the attic. When one of the watchmen trips the silent alarm, the criminals narrowly escape with their prisoner before the police arrive. Franz, one of the criminals, is left behind in the confusion and captured by the police; Lohmann tricks him into admitting that the gang only broke into the building to find Beckert and revealing where he will be taken.[12]

The criminals drag Beckert to an abandoned distillery to face a kangaroo court. He finds a large, silent crowd awaiting him. Beckert is given a 'lawyer', who gamely argues in his defense but fails to win any sympathy from the improvised 'jury'. Beckert delivers an impassioned monologue, saying that he cannot control his homicidal urges, while the other criminals present break the law by choice, and further questioning why they as criminals believe they have any right to judge him by stating: 'What right have you to speak? Criminals! Perhaps you are even proud of yourselves! Proud of being able to crack into safes,[13] or climb into buildings or cheat at cards. All of which, it seems to me, you could just as easily give up, if you had learned something useful, or if you had jobs, or if you were not such lazy pigs. I can not help myself! I have no control over this evil thing that is inside me – the fire, the voices, the torment!'[14]

Beckert pleads to be handed over to the police, asking: 'Who knows what it is like to be me?'. His 'lawyer' points out that the presiding 'judge' is wanted on three counts of Totschlag (manslaughter, a form of homicide in German law), and that it is unjust to execute an insane man. Just as the enraged mob is about to kill Beckert, the police arrive to arrest both him and the criminals.

As a panel of judges prepares to deliver a verdict at Beckert's real trial, the mothers of three of his victims weep in the gallery. Elsie's mother says that 'No sentence will bring the dead children back', and that 'One has to keep closer watch over the children'. The screen fades to black as she adds, 'All of you'.[15]

Cast[edit]

- Peter Lorre as Hans Beckert. M was Lorre's first major starring role, and it boosted his career, even though he was typecast as a villain for years afterward in films such as Mad Love and Crime and Punishment. Before M, Lorre had been mostly a comedic actor. After fleeing from the Nazis he landed a major role in Alfred Hitchcock's first version of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), picking up English along the way.[16]

- Otto Wernicke as Inspector Karl Lohmann. Wernicke made his breakthrough with M after playing many small roles in silent films for over a decade. After his part in M he was in great demand due to the success of the film, including returning to the role of Karl Lohmann in The Testament of Doctor Mabuse, and he played supporting roles for the rest of his career.[17]

- Gustaf Gründgens as Der Schränker (The Safecracker). Gründgens received acclaim for his role in the film and established a successful career for himself under Nazi rule, ultimately becoming director of the Staatliches Schauspielhaus (National Dramatic Theatre).[18]

|

|

Production[edit]

Lang placed an advert in a newspaper in 1930 stating that his next film would be Mörder unter uns (Murderer Among Us) and that it was about a child murderer. He immediately began receiving threatening letters in the mail and was also denied a studio space to shoot the film at the Staaken Studios. When Lang confronted the head of Staaken Studio to find out why he was being denied access, the studio head informed Lang that he was a member of the Nazi party and that the party suspected that the film was meant to depict the Nazis.[20] This assumption was based entirely on the film's original title and the Nazi party relented when told the plot.[21]

M was eventually shot in six weeks at a Staaken Zeppelinhalle studio, just outside Berlin. Lang made the film for Nero-Film, rather than with UFA or his own production company. It was produced by Nero studio head Seymour Nebenzal who later produced Lang's The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Other titles were given to the film before 'M' was chosen; Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder (A City searches for a Murderer) and Dein Mörder sieht Dich an (Your Murderer Looks At You).[22] While researching for the film, Lang spent eight days inside a mental institution in Germany and met several child murderers, including Peter Kürten. He used several real criminals as extras in the film and eventually 25 cast members were arrested during the film's shooting.[23] Peter Lorre was cast in the lead role of Hans Beckert, acting for the film during the day and appearing on stage in Valentine Katayev's Squaring the Circle at night.[24]

Lang did not show any acts of violence or deaths of children on screen and later said that by only suggesting violence, he forced 'each individual member of the audience to create the gruesome details of the murder according to his personal imagination'.[25]

M has been said, by various critics and reviewers,[26] to be based on serial killer Peter Kürten—the Vampire of Düsseldorf—whose crimes took place in the 1920s.[27] Lang denied that he drew from this case, in an interview in 1963 with film historian Gero Gandert; 'At the time I decided to use the subject matter of M, there were many serial killers terrorizing Germany—Haarmann, Grossmann, Kürten, Denke, [...]'.[28][29] Inspector Karl Lohmann is based on then famous Ernst Gennat, director of the Berlin criminal police.[30]

Leitmotif[edit]

M was Lang's first sound film and Lang experimented with the new technology.[31] It has a dense and complex soundtrack, as opposed to the more theatrical 'talkies' being released at the time. The soundtrack includes a narrator, sounds occurring off-camera, sounds motivating action and suspenseful moments of silence before sudden noise. Lang was also able to make fewer cuts in the film's editing, since sound effects could now be used to inform the narrative.[32]

The film was one of the first to use a leitmotif, a technique borrowed from opera, associating a tune with Lorre's character, who whistles the tune 'In the Hall of the Mountain King' from Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt Suite No. 1. Later in the film, the mere sound of the song lets the audience know that he is nearby, off-screen. This association of a musical theme with a particular character or situation is now a film staple.[33] Peter Lorre could not whistle and Lang himself is heard in the film.[34]

Release and reception[edit]

M premiered in Berlin on 11 May 1931 at the UFA-Palast am Zoo in a version lasting 117 minutes.[24] The original negative is preserved at the Federal Film Archive in a 96-minute version. In 1960, an edited 98-minute version was released. The film was restored in 2000 by the Netherlands Film Museum in collaboration with the Federal Film Archive, the Cinemateque Suisse, Kirsch Media and ZDF/ARTE., with Janus Films releasing the 109-minute version as part of its Criterion Collection using prints from the same period from the Cinemateque Suisse and the Netherlands Film Museum.[35] A complete print of the English version and selected scenes from the French version were included in the 2010 Criterion Collection releases of the film.[36]

The film later was released in the U.S. in April 1933 by Foremco Pictures.[37] After playing in German with English subtitles for two weeks, it was pulled from theaters and replaced by an English-language version. The re-dubbing was directed by Eric Hakim, and Lorre was one of the few cast members to reprise his role in the film.[24] As with many other early talkies from the years 1930–1931, M was partially reshot with actors (including Lorre) performing dialogue in other languages for foreign markets after the German original was completed, apparently without Lang's involvement. An English-language version was filmed and released in 1932 from an edited script with Lorre speaking his own words, his first English part. An edited French version was also released but despite the fact that Lorre spoke French his speaking parts were dubbed.[38]

A Variety review said that the film was 'a little too long. Without spoiling the effect—even bettering it—cutting could be done. There are a few repetitions and a few slow scenes.'[24]Graham Greene compared the film to 'looking through the eye-piece of a microscope, through which the tangled mind is exposed, laid flat on the slide: love and lust; nobility and perversity, hatred of itself and despair jumping at you from the jelly'.[25]

In later years, the film received mostly positive reviews from critics and currently holds an approval rating of 100% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 53 reviews, with a weighted average of 9.24/10. The site's critics consensus reads: 'A landmark psychological thriller with arresting images, deep thoughts on modern society, and Peter Lorre in his finest performance.'[39]

In 2013, a DCP version was released by Kino Lorber and played theatrically in North America[40] in the original aspect ratio of 1.19:1.[41] Critic Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times called this the 'most-complete-ever version' at 111 minutes.[42] The film was restored by TLEFilms Film Restoration & Preservation Services (Berlin) in association with Archives françaises du film - CNC (Paris) and PostFactory GmbH (Berlin).[43]

Legacy[edit]

Lang considered M to be his favorite of his own films because of the social criticism in the film. In 1937, he told a reporter that he made the film 'to warn mothers about neglecting children'.[31]

A scene of the movie was used in the 1940 Nazi propaganda movie The Eternal Jew.[44]

A Hollywood remake of the same name was released in 1951, shifting the action from Berlin to Los Angeles. Nero Films head Seymour Nebenzal and his son Harold produced the film for Columbia Pictures. Lang had once told a reporter 'People ask me why I do not remake M in English. I have no reason to do that. I said all I had to say about that subject in the picture. Now I have other things to say.'[23] The remake was directed by Joseph Losey and starred David Wayne in Lorre's role. Losey stated that he had seen M in the early 1930s and watched it again shortly before shooting the remake, but that he 'never referred to it. I only consciously repeated one shot. There may have been unconscious repetitions in terms of the atmosphere, of certain sequences.'[23] Lang later said that when the remake was released he 'had the best reviews of [his] life'.[25]

The original 1931 M was ranked at number 33 in Empire magazines 100 Best Films of World Cinema in 2010.[45]

In 2003, M was adapted for radio by Peter Straughan and broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on February 2, later re-broadcast on BBC Radio 4 Extra on 8 October 2016.[46] Directed by Toby Swift, this drama won the Prix Italia for Adapted Drama in 2004.[citation needed]

Jon J. Muth adapted the screenplay into a four part comic book series in 1990, which was reissued as a graphic novel in 2008.[47]

See also[edit]

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

References[edit]

- ^'M (A)'. British Board of Film Classification. 24 May 1932. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^'Now I Lay Me Down To Sleep: A Brief History of Child Murder in Cinema'. Bloody Disgusting!. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^Monsters of Weimar p. 296

- ^Monsters of Weimar pp. 296-298

- ^Reader Archive-Extract: 1997/970808/M[permanent dead link]

- ^Kauffman, Stanley. 'The Mark of M'. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^While the location is never mentioned in the film, the dialect used by the characters is characteristic of Berliners, and a police inspector's map labeled 'Berlin' and a policeman's order to take a suspect to the 'Alex', Berlin's central police headquarters on the Alexanderplatz, make the venue clear.

- ^'Fritz Lang's M: the Blueprint for the Serial Killer Movie'. bfi.org.uk.

- ^'Fritz Lang's M: the Blueprint for the Serial Killer Movie'. bfi.org.uk. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^Bradshaw, Peter (4 September 2014). 'M review – Fritz Lang's superb thriller fascinates'. The Guardian.

- ^ abMonsters of Weimar p. 297

- ^'M'.

- ^'M (1931)'. classicartfilms.com.

- ^Monsters of Weimar p. 298

- ^Garnham, Nicholas (1968). M: a film by Fritz Lang. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 15–108. ISBN9780900855184.

- ^Erickson, Hal. 'Biography'. Allmovie. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^Staedeli, Thomas. 'Otto Wernicke'. Cyranos. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^Staedeli, Thomas. 'Otto Wernicke'. Cyranos. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^Garnham. p. 13.

- ^Jensen, Paul M.. The Cinema of Fritz Lang. New York: A. S. Barnes & Co.. 1969. SBN 498 07415 8. pp. 93

- ^Wakeman, John. World Film Directors, Volume 1. New York: The H. W. Wilson Company. 1987. ISBN0-8242-0757-2. pp. 614.

- ^Jensen. pp. 93

- ^ abcJensen. pp. 94.

- ^ abcdJensen. pp. 93.

- ^ abcWakeman. pp. 615.

- ^Ramsland, Katherine. 'Court TV Crime Library Serial Killers Movies'. Crime Library. Archived from the original on 3 November 2006. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- ^Morris, Gary. 'A Textbook Classic Restored to Perfection'. Bright Lights. Retrieved 12 January 2007.

- ^'Fritz Lang on M: An Interview', in Fritz Lang: M—Protokoll, Marion von Schröder Verlag, Hamburg 1963, reprinted in the Criterion Collection booklet.

- ^Monsters of Weimar p. 293

- ^Kempe,Frank: “Buddha vom Alexanderplatz“, Deutschlandfunk Kultur, 21 August 2014 (in German).

- ^ abJensen. pp. 95.

- ^Jensen. pp. 103.

- ^Costantini, Gustavo. 'Leitmotif revisited'. Filmsound. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- ^Falkenberg, Paul (2004). 'Classroom Tapes — M'. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- ^M, Janus Films, Criterion Collection, closing credits.

- ^Review of 2010 M Blu-ray/DVD release (region 2), DVD Outsider.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ^'The Daesseldorf Murders'. New York Times. 3 April 1933. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^'DVD Extra: Peter Lorre's long-lost English-language debut'. New York Post. 4 March 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^'M (1931)'. Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^Erik McLanahan (9 April 2013). 'Fritz Lang's 'M' is a great entertainment, but it's also a genre mashup'. Oregon Artswatch. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^'M (Thursday 9PM)'. The Charles Theater [Baltimore, Maryland]. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^Kenneth Turan (9 April 2013). 'Critic's Choice: 'M' stands for masterpiece'. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^'M'. Kino Lorber. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^Barnouw, Erik (1993). Documentary: a history of the non-fiction film. Oxford University Press. p. 142. ISBN978-0-19-507898-5. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^'The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema: 33. M'. Empire.

- ^'Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou - M - BBC Radio 4 Extra'. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^'Fiction Book Review: M: A Graphic Novel by Jon J. Muth, Author, Thea Von Harbou, Screenplay by, Fritz Lang, Adapted by . Abrams $24.95 (189p) ISBN 978-0-8109-9522-2'.

Cited words and further reading[edit]

- Lessing, Theodor (1993) [1925]. Monsters of Weimar: Haarmann, the Story of a Werewolf. London: Nemesis Books. pp. 293–306. ISBN1-897743-10-6.

- Thomas, Sarah (2012). Peter Lorre, Face Maker: Stardom and Performance Between Hollywood and Europe. United States: Berghahn Books. ISBN978-0-857-45442-3.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: M (1931 film) |

- M is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- M on IMDb

- M at AllMovie

- M at the TCM Movie Database

- The Restoration of M (2003) from TLEFilms.com

- The Mark of M an essay by Stanley Kauffmann at the Criterion Collection